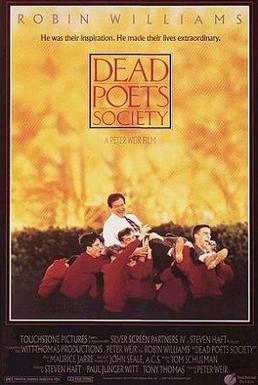

Two of my students presented an analysis of Dead Poets Society today in class. Although I have seen the movie several times, there is a point that is not frequently considered in reviews of such movies. Talk is often made about the role of the teacher, John Keating (Robin Williams), and the constructivist, student-centered perspective that he used. His animation and energy for life and teaching are often emphasized. However, less talk is often centered around the role of the students in this classroom environment. Specifically, talk of their reluctance (at least initially) to conform to new, innovative, out-of-the-box teaching practices is not usually given as much attention or thought. Nevertheless, this perspective is one that many teachers today are facing as they are seeking to advocate the use of technology in their schools.

Two of my students presented an analysis of Dead Poets Society today in class. Although I have seen the movie several times, there is a point that is not frequently considered in reviews of such movies. Talk is often made about the role of the teacher, John Keating (Robin Williams), and the constructivist, student-centered perspective that he used. His animation and energy for life and teaching are often emphasized. However, less talk is often centered around the role of the students in this classroom environment. Specifically, talk of their reluctance (at least initially) to conform to new, innovative, out-of-the-box teaching practices is not usually given as much attention or thought. Nevertheless, this perspective is one that many teachers today are facing as they are seeking to advocate the use of technology in their schools. Students of all ages may see relevance for using technology in their everyday life. However, they may see less purpose for allowing such innovation to be used as a teaching tool. They look around the room and at each other, seeming to question the fact that technology could be used within the context of learning other relevant content.

Sure, there is the perception that all of our students are digital natives, living and breathing with technology. However, this is not always true. They, like many teachers, have to learn technological skills (e.g., Web 2.0 tools). Likewise, they want to see the purpose behind the technological use (i.e., technology integration).

Certainly, it is an interesting age in which we live. Many educators and citizens want to see positive school reforms implemented -- especially such reforms that embrace technology. However, the change is likely going to be a gradual process. eSchoolnews offers some survey results related the barriers of Web 2.0 is schools.

What do you think? Are students a barrier or a catalyst to technology integration in your school?